|

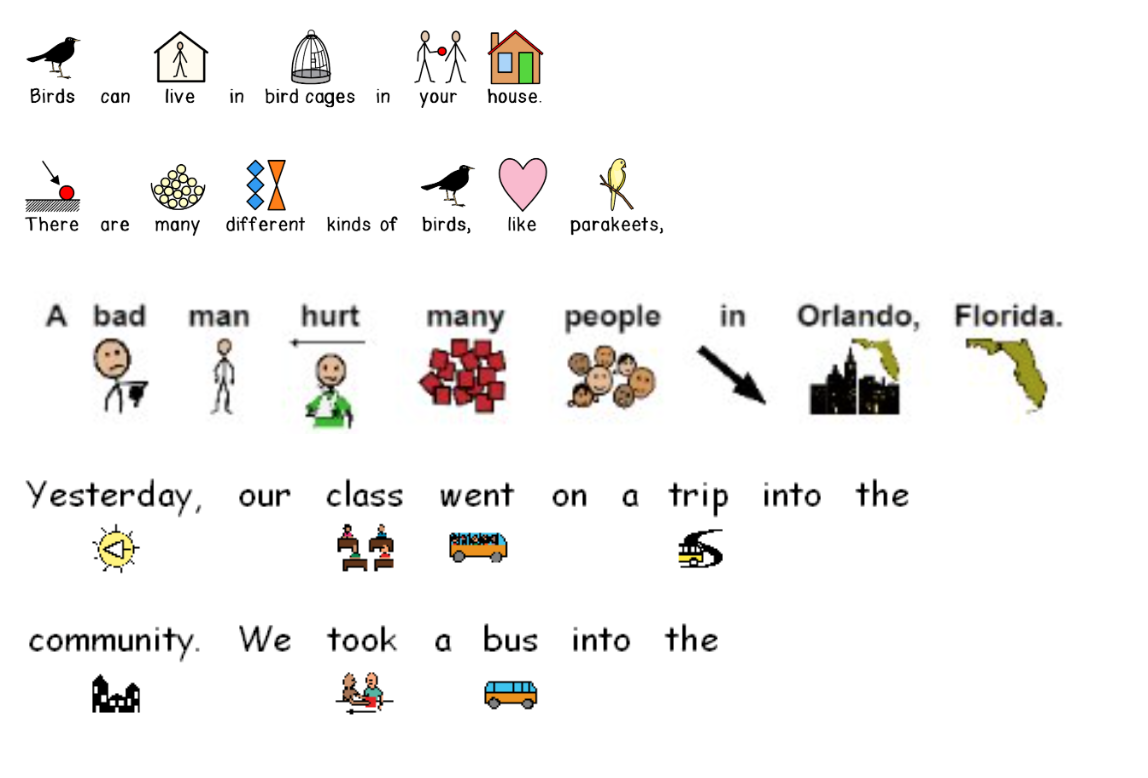

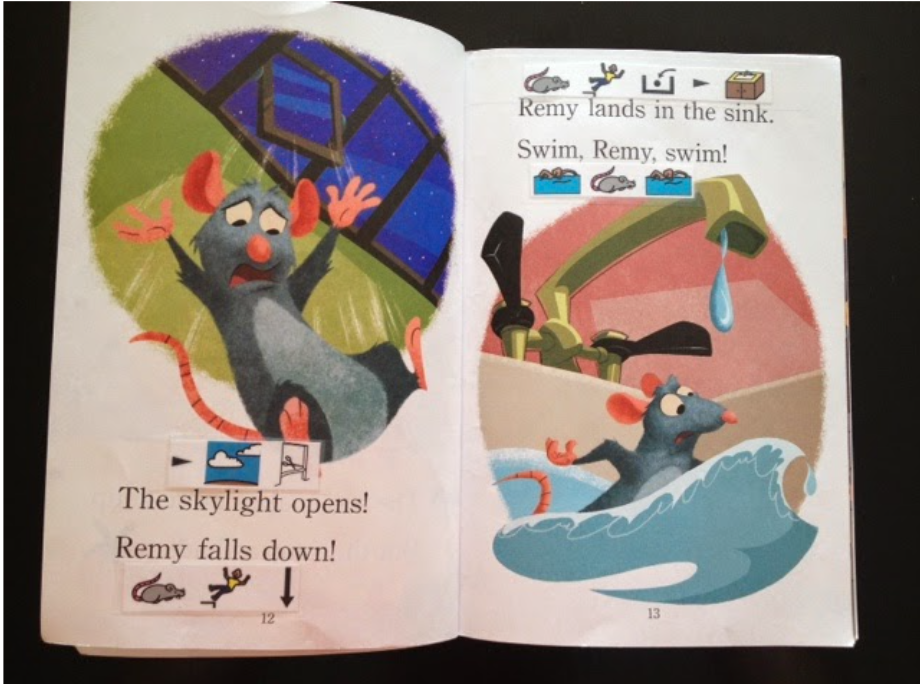

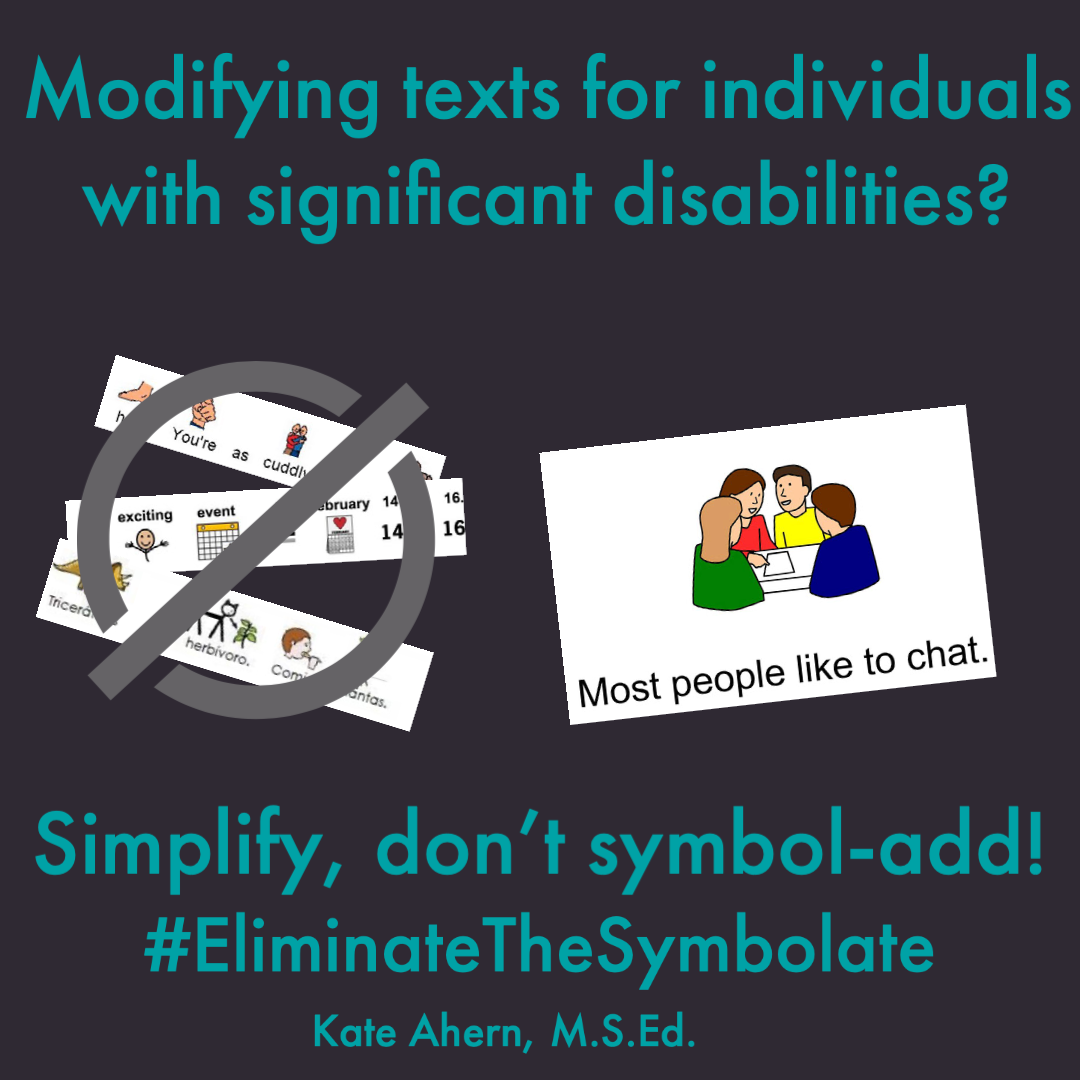

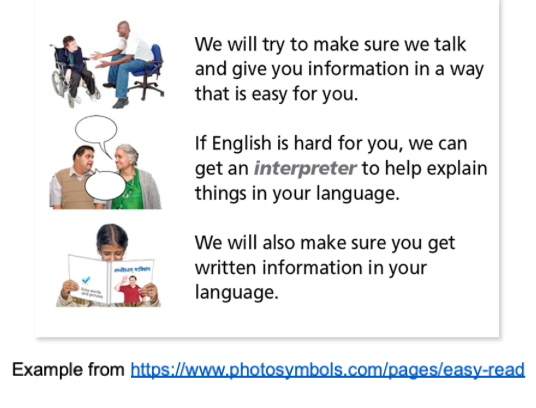

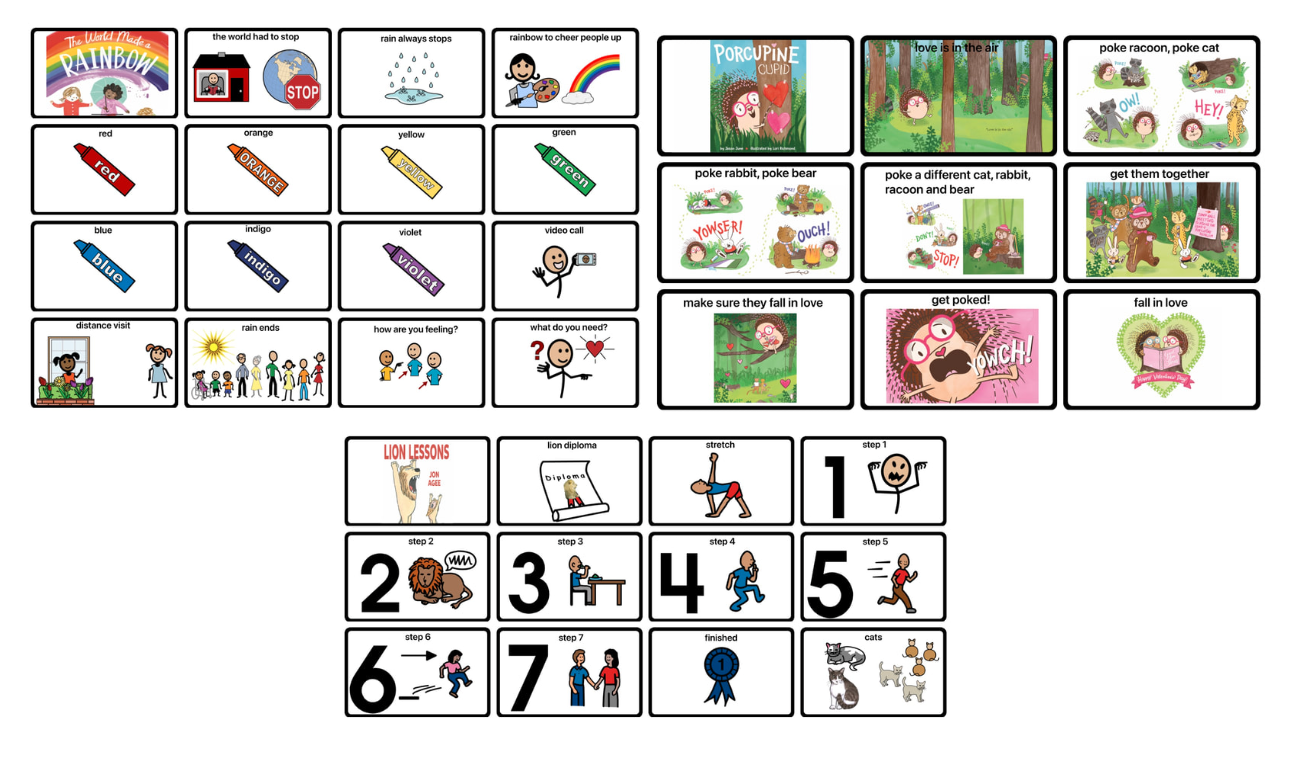

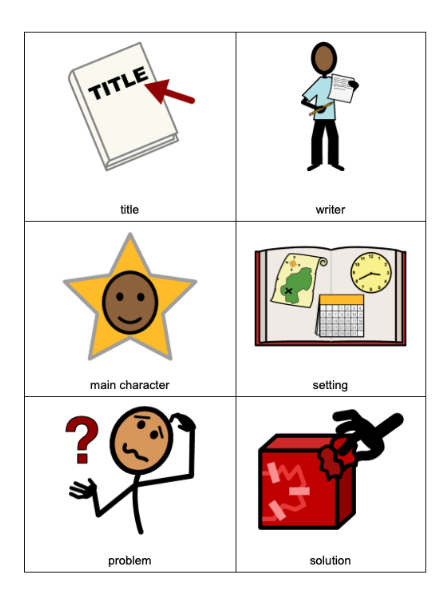

Symbol Supported Text, sometimes called Symbolated Text, is the practice of adding picture symbols above or below each word or phrase in text based materials meant to be read. (It does not apply to symbols in AAC systems.) Here are some examples: As you can see symbols from a variety of companies are placed above or below the written text. If you look at the symbols alone, as a non-reader would do, it is very difficult to know what is being said. The first example might be read as “bird home bird cage give house” to an unfamiliar person. The second might be read as “bad person broken arm lots people down Florida city, Florida”. The final might be read as “left class bus road city take bus”. The symbols do little to nothing to improve understanding. They also distract from reading the actual text. There is essentially no research indicating that this practice improves the understanding of these texts by individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (IDD) or by individuals with IDD and complex communication needs (CCN). In fact there is study that shows typical adults cannot guess meaning from supporting symbols. Most “evidence'' supporting this claim has been created by the companies which sell products to create symbol supported text or which sell products featuring symbol supported text (Example of such companies include Widgit, Symbol Inclusion Project, Tobii Dynavox Boardmaker, Slater Software, News2You. Vendors like those on TeachersPayTeachers such as Breezy Special Ed, A Special Kind of English, and Winter’s Wonderful Workers will often cite this commercial research when told their products are detrimental to learning literacy.) There is also specific research, which is done by neutral parties, saying that the addition of symbols doesn’t increase comprehension. Still, the practice of symbol supported text remains very common in special education, despite years of evidence that it is not beneficial. Many teachers, therapists and caregivers make anecdotal claims of symbol supported text increasing comprehension but the research just isn’t there. However, Symbol Supported Text can be a lot worse than just the time and money wasted on adapting or purchasing materials which do not increase understanding. Symbol Supported Text, in fact any image or symbol paired with a word, has been shown to either have no impact or to be detrimental to children learning to read. Studies have looked at programs that explicitly pair carefully chosen symbols with a word and have found that when the symbols are removed from the word children do not retain the ability to identify the word. Children who learned symbols paired with text did not attend to or attempt to decode words when the symbol was present and could not read the word when the symbol was removed. As one can imagine, haphazardly pairing words with symbols would be even worse for learning to read, especially when large groups of words are presented simultaneously in a manner which is visually cluttered, and symbols might change meaning regardless of the word with which it is paired. (See the example below where the same symbol is used for “falls” and “lands”. ,If you are interested in reading relevant, non-commercial research, I suggest starting with this article by Erickson, Hatch and Clendon https://bit.ly/3yXY0k6, specifically the section entitled “Picture Supported Text: An Example” and Comprehensive Literacy for All by Erickson and Koppenhaver, especially the section entitled “Research Brief: Assistive Technology” https://amzn.to/3wJkIL8. Additional research information can be found at the end of this article. Unfortunately, many professionals and caregivers refuse to consider the significant evidence that symbol supported text is detrimental to learning to read because they do not consider their students as candidates for literacy. This ableist view comes from a tyranny of low expectations and a lack of knowledge about how to teach literacy at all, but especially to learners with IDD and/or CCN. It is horrifying to say it aloud, but professionals who use symbol supported text often do so because it makes them feel they are doing something when, in reality, they are refusing comprehensive literacy instruction to their students. Instead schools and professionals should be fully committing to literacy instruction for all learners, regardless of perception of cognitive ability. As Dr. David Yoder says, “No student is too anything to be able to read and write.” It is difficult as experienced professionals to face what this means. If we have not taught literacy and have only used symbol supported text and done listening comprehension we may feel guilty and defensive when someone suggests that we should have been teaching literacy all along and that we shouldn't have been using symbol supported text. It is a terrible feeling to think maybe we failed our former students. Facing that guilt is incredibly difficult. However, we can remind ourselves that we did the best we could with the information we had at the time. We must be brave enough as professionals to learn new information, evaluate it and incorporate it into our practice. As the old saying goes, "know better, do better". We are capable of changing course and making sure the students in front of us from this day forward get literacy instruction. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom and Australia, a common practice, sometimes a legally mandated practice, is called “Easy Read” materials. These places have created guidelines on how to make text based materials more accessible to those with IDD and/or CCN as well as people with other disabilities, English language learners and the elderly. For example, guidelines for the United Kingdom can be found here and here for New Zealand and here for Australia. Special educators, therapists and others can draw from the Easy Read guidelines and emerging research on Easy Read to help them adapt text in ways that promote both comprehension and learning to read. Some of the big ideas are to use clear, simple language, to limit each sentence to one concept and consider having only one concept per section or page, to use images and symbols to illustrate these concepts (rather than matching picture symbols to words), and to use specific formats. Simplify the Text Simplifying text means using easily understood vocabulary and simple sentence constructions to present important concepts. Simplifying text works best when teachers are adapting text based materials to create an entirely new material. This is most useful when there is a large gap between the individual's comprehension skills and the complexity of the text. One technology tool available for this is Rewordify. Rewordify is a free tool allowing you to enter/copy & paste text into the program and then lower the reading level and identify vocabulary to be simplified. This process of simplifying text is not likely to be as effective for picture books where modifying the text would change the experience of the book. Simplify the Format The format of text can be beneficial or detrimental to comprehension of that text. Use of 14+ font in a clear font such as arial can make text more accessible. Text size can be increased if needed for those with visual or attentional needs. It is recommended to have one concept or idea per sentence or line. In some cases this may be one concept or idea per page. The website Tar Heel Reader and the app Pictello by AssistiveWare are both good examples of tools which help adapt materials to present one idea or concept per page. Easy Read guidelines recommend consistent placement of images either on the right or left side of the page if there will be multiple images on a page, with the correlating text next to it. Layout should be clear and simple, as well as consistent, across sections or pages. A Word about Picture Books Picture books are the perfect teaching and engagement tool exactly as they come. Depending on the level of book you choose it may have images and simple text perfect for working on literacy and comprehension skills. When we glue or tape in picture symbols or symbol supported text we are likely not improving comprehension, we are detracting from the perfection that is a picture book including the images and text, and we are limiting the ability of students to focus on letters and words and attempt decoding text. AAC User Specific Suggestions for Picture Books There are some specific recommendations for shared reading of picture books with AAC users/individuals with CCN. The first thing to do is to read through the picture book and identify the core words or other specific vocabulary you will model using aided language stimulation on the individual's AAC system. Words to be targeted can be underlined in pencil or listed on a post-it note on each page. It is vital not to tape or glue in strips of symbol supported text as that is not shown to aid comprehension and is likely to be detrimental to learning to read. Educators and Therapists may also wish to create a visual support to be used with the book. There are many ways to do this, such as creating a document which notes occurrences in the story in sequence for individuals to check off as they happen. Pictured below are visual supports for three picture books. Each has the title and then, moving right to left, top to bottom, symbols or images about the sequence of events in the book. Students can check off each box as it occurs in the story and/or use the visual support to aid them in answering comprehension questions or retell the story. Symbols or images on a separate visual support is preferable from gluing or taping in symbols to go with the text. Another option is to have cards or visual displays with pictures or picture symbols of important characters, occurrences and vocabulary in the book to hold up or hand around as you need. These can be combined with sensory items for learners who respond well to sensory materials or who have visual disabilities. Similarly, you can have a card of picture symbols or a chart of story elements to use as you read to guide the students in thinking about what the elements of that specific are. Visual schedules of the steps in a reading activity can also be used to help students know what is happening and what will happen next. Graphic Organizers are another tool which can be used to increase comprehension. Commercially made graphic organizers are available in many formats and designs or professionals can create their own. There are many types of graphic organizers for reading comprehension. Story Maps are one tool to help in fiction picture book reading. Students who do not yet write can use their AAC system to dictate how to fill in the characters (use core words like girl or bear), setting (time and place), the problem and the solution in the story. A variety of options are available for describing characters or comparing and contrasting characters or books. Summarizing graphic organizers following a format of "someone", "wanted", "but", "so", "finally" are also enticing to learners who use AAC to complete with in a group setting. For non-fiction picture books KWL or Know, Wonder, Learned charts can be created so students can list, via their AAC system what they already know about the subject and what they wonder at it it; after reading they can add what they learned from the book. All of these activities, based around graphic organizers, can be adapted to match the skills of a wide range of learners and increase understanding of fiction stories or the topic of a non-fiction book, teach the skills for understanding how books work and encourage use of AAC systems. Finally, Smart Charts are a tool that can be used to support professionals and paraprofessionals in modeling language through aided language stimulation on AAC systems or as visual supports for AAC users to find words in their systems. Smart Charts can be created for vocabulary in picture books and stored in the books or displayed when the book is read. More information on aided language stimulation can be found online and in the book Comprehensive Literacy for All by Erickson and Koppenhaver. One part of aided language stimulation during shared reading is to comment, ask and respond (CAR). Using this technique will increase comprehension of the text as well as help develop AAC skills, and are much more reliable than symbol supported text. Adapting Stand Alone Text

Writing Style

Vocabulary

Formatting

Images/Symbols

Adapting Picture Books

Benson-Goldberg & Erickson, 2020, Graphic Symbols: Improving or Impeding Comprehension of Communication Bill of Rights? Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits Volume 14, Spring 2020, pp. 1-18 Available online: www.atia.org/atob Blischak, D. M., & McDaniel, M. A. (1995). Effects of picture size and placement on memory for written words. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 1356-1362. Erickson, K.A., Hatch, P. & Clendon, S. (2010). Literacy, Assistive Technology, and Students with Significant Disabilities. Focus on Exceptional Children, 42(5), 1 – 16. https://literacyforallinstruction.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Literacy_Assistive_Technology_and_Students_with_Si.pdf Farrell, J Symbol Supported Text: Does it Really Help?https://www.janefarrall.com/symbol-supported-text-does-it-really-help/ Fossett and Mirenda (2006) Sight word reading in children with developmental disabilities: A comparison of paired associate and picture-to-text matching instructionResearch in Developmental Disabilities Volume 27, Issue 4, July–August 2006, Pages 411-429 Hatch. P. (2009). The effects of daily reading opportunities and teacher experience on adolescents with moderate to .severe intellectual disability. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Poncelas & Murphy (2006) Accessible Information for People with Intellectual Disabilities: Do Symbols Really Help? Journal for Research in Intellectual Disabilties 14 March 2007 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00334 Pufpaff, L. A., Blischak, D. M., & Lloyd, L. L. (2000). Effects of mod- ified orthography on the identification of printed words. American Jounial on Mental Retardation, 105(\), 14-24. Rose, T. L., & Furr, P. M. (1984). Negative effects of illustrations as word cues. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 17(6), 334-337. Samuels, J. (1967). Attentional processes in reading - The effects of pictures on the acquisition of reading responses. Minneapolis:University of Minnesota. (ERIC Clearinghouse ED014370). Saunder, R, J., & Solman, R, T. (1984). The effect of pictures on the acquisition of a small vocabulary of similar sight-words. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 54(?\), 265-275. Singer, H., Samuels, S. J., & Spiroff, J. (1973-1974). The effects of pictures and contextual conditions on learning responses to printed words. Reading Research Quarterly, 9(4), 555-567. Singh, N. N., & Solmon, J. (1990). A stimulus control analysis of the picture-word problem in children who are mentally retarded: The blocking effect. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23, 525-532.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed